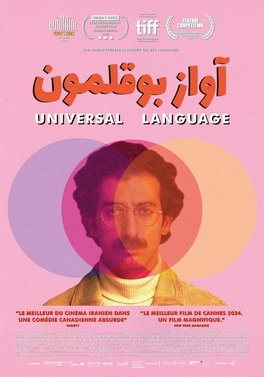

“Universal Language” is the second feature film from experimental Candian director Mathew Rankin. Rankin’s previous film, “The Twentieth Century” (2019), holds a special place in my heart and is often my go-to litmus test for people’s tolerance of weirdness. It is not that “The Twentieth Century” is only weird; it just happens to be expressive, such to a degree that those heavily moored to narrative and tonal conventionalities may not be able to appreciate its genius. “Universal Language” is a bit closer to the world we know but still shares many of these characteristics.

When interviewed at TIFF about “Universal Language,” Rankin said he was “skeptical of the possibility of authenticity” of cinema. In his films, he embraces the layer of artifice that less experimental directors try to erase. “The Twentieth Century” thickened that layer between reality and artifice by throwing us into a German Expressionist dream of exaggerated performances and bold colors. Similarly, “Universal Language” presents a world where Winnipeg is an Irano-Canadian hybrid, forever encased in snow, with only cold, dominated by midcentury grey or brown brick buildings.

The visuals of “Universal Language” again nod to a cinematic movement, not German Expressionism this time, but the Iranian New Wave. Cinematographer Isabelle Stachtchenko uses Super 16 film, and the unique color pattern of the visible grain resulting from this choice does much to wash away modernity from Winnipeg and return us, if not to Tehran, maybe halfway there. Natural lighting is employed throughout the film to give a false sense of realism that was not present at all in “The Twentieth Century.” The grit of the 16mm film, the brightness of the natural lighting and snow, and the coldness of the architecture and snow all work together to highlight the warmth of human interaction.

Another way “Universal Language” differs from Rankin’s previous film is in its quiet intimacy. In line with the Iranian new wave films “Universal Language” idealizes, the plot features several slowly intertwining, small, intimate stories. Pirouz Nemati plays Massoud, a tour guide leading visitors through Winnipeg’s unconventional landmarks. Massoud leads mostly uninterested tourists through the brick-and Brutalist blocks to uneventful landmark after uneventful landmark. Where Brutalism might have represented permanence and perseverance to László Tóth, it provides a grey backdrop that highlights the vibrancy of our characters. Negin (Rojina Esmaeili) and Nazgol (Saba Vahedyousefi) are two girls attempting to retrieve a frozen banknote in another storyline. Our final plot thread features Ranking playing himself, which he has acknowledged as a nod to Abbas Kiarostami’s Close-Up, himself displacing and seeking human connection alongside the girls and Massoud. Each character is searching for something that seems lost; for Massoud, neglected or obscure landmarks fail to entertain visitors, Negin and Nazgol search endlessly for a way to crack out the money, and Mathew Rankin seeks to find and reconnect with his mother. All seem to be in the wrong place at the wrong time until they finally come together.

Rankin’s work continues to be an incredibly heartfelt and rewarding cinematic experience. When interviewed at TIFF about Universal Language, Rankin said he was ‘skeptical of the possibility of authenticity’ in cinema. Rather than striving for realism, he embraces artifice. “Universal Language” pairs that trait with intimate storytelling, quiet reflection, and Super 16 borrowed from the Iranian New Wave. On its surface, this combination may seem paradoxical, but the result is a metafictional piece that can warm the coldest Winnipeg day.